Hollywood Carter

Look Horses: Part IV

Look Horses: Some Equine Histories of Los Angeles is a multi-part series both about horses in the Southland and not. This is part four.

HOLLYWOOD PARK

“And now, ladies and gentlemen, Hollywood Park belongs to you,” said racing announcer Joe Hernandez to Al Jolson, Joan Crawford, Milton Berle, Claudette Colbert, Bob Hope, Barbara Stanwyck, and 40,000 other, everyday Southern Californians attending the opening day of Hollywood Park Racetrack.

From June 10, 1938, until December 22, 2013, the grounds at 1000–1050 South Prairie Avenue in Inglewood, California, were home to a thoroughbred racetrack critics considered architecturally “beautiful almost beyond description.”

Bill Henry, columnist for the Los Angeles Times, described Hollywood Park as “fine as anyone could imagine, and they’ve even got a chain of lakes out in the infield with swans paddling about in the dignified manner of their kind and setting a fine example of placid contentment to the jittery two-dollar bettors.”

In this way, like Wimbledon, Hollywood Park was a cathedral of our sport.

But Hollywood Park was of its time, and had its time.

On May 31, 2015, nearly seventy-seven years of history were reduced to rubble in less than thirty seconds—a spectacle cheered by fans chanting “LA Rams,” willing their promised stadium to rise from Hollywood Park’s imploded grandstand.

In the decade since, the grounds at 1000–1050 South Prairie Avenue in Inglewood have been developed into “new sophisticated residences” and a “modern open-office campus” to complement the entertainment and retail district surrounding the two “premiere sports and entertainment venues,” specifically the 6,000-seat YouTube Theater and the 77,000-seat home of Los Angeles’ two pro football teams, SoFi Stadium.

Michele Asselin documented the final weeks of Hollywood Park in her book, Clubhouse Turn: The Twilight of Hollywood Park, a collection of nearly three hundred images published by Angel City Press, and a major inspiration for this series, Look Horses.

Asselin’s photographs ask, “How is a building like a face?” The images consider whether the path between an internal existence and its external presentation traces the society of which it's a part, finding that a society is reflected in the details of its buildings as much as the faces of its people.

It’s May 16, 2025, and Mandarette Cafe, The Original Pantry Cafe, and Papa Cristo’s Greek Grill are gone. Du-Par’s and Chili John’s are struggling.

Who will we be when LA’s built environment no longer has a reflection?

COWBOY CARTER

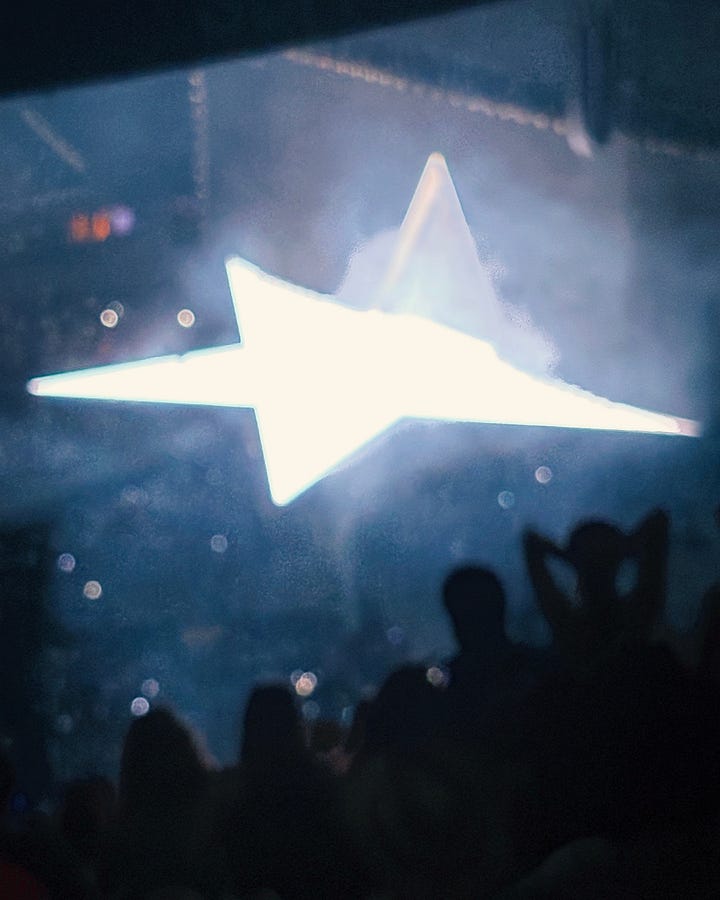

Eleven years and two days since Jay-Z and Solange’s infamous elevator fight, the 110 was a parking lot from Stadium Way to 190th Street. Hours later, in the second-to-last row in the highest section of SoFi Stadium as cowboy hats glittered in the crowd and stars floated across the stage, it was a little like seeing God.

Except it wasn’t God, it was Beyoncé. It was Beyoncé on the fourth night of her Cowboy Carter Tour.

SoFi Stadium itself is unremarkable. A massive starship of a building wholly lacking otherworldly qualities instead possesses a certain pumpkin spice austerity: a teenage son dreams of Cybertrucks in a Nancy Meyers kitchen.

The building is empty in its bones but filled with light, bright bursts from the syncopated bracelets given out at entry. With the sheer thrill of so many enthralled, decked out in denim, white leather, snakeskin boots, rhinestones, chaps, and tasseled hats—their cowboy best—to celebrate the night. The stadium is full, and finally feels alive with a devotion and pageantry rivaled only by the recent papal conclave.

Cowboy Carter is Beyoncé’s Grammy-award-winning, CMA-snubbed country album. After years of stupid dorks ham-fistedly interpolating hip-hop into country music, Beyoncé made something with a stronger sense of time and place. Nancy Sinatra is chopped and screwed, the Beach Boys’ plea for good vibrations is Beyoncé’s demand. Never ask permission for something that already belongs to you.

Two years ago, Beyoncé took a victory lap with her Renaissance World Tour, a celebration of underground nights, of the club, and this tour incorporates some set pieces in their entirety. Despite critiques, it is not hard to keep Renaissance and Cowboy Carter in conversation with one another. Certainly, genres are a funny little concept, as Linda Martell reminds us over the Jumbotron.

When coupled with Renaissance’s Chicago and Detroit house and techno, the Cowboy Carter Tour is certainly less country western—and more a chronicle of Black America’s contributions to this musical landscape. In this way, it is Country.

You could imagine horses running here.