Both Here and Now

Look Horses: Part VI

Look Horses: Some Equine Histories of Los Angeles is a multi-part series both about horses in the Southland and not. This is part six.

Sanita Anita Park is filled with people, both here and now. Long hallways of people filter in and out, horses led through tunnels, a child makes her breakaway to the carnival on the infield. A space that has seen thousands and thousands of people and animals through decades and decades and decades. Their footfalls still linger here. A racetrack can be more than a racetrack.

It could be a home. There are the jockeys and owners and trainers and the crew who live temporarily on the grounds in little green bungalow apartments. Put up in tight corners before race day.

It could be a prison. For artist Ruth Asawa and 19,000 Japanese Americans, it was.

Santa Anita became a temporary internment camp during World War II, as the US built more permanent prisons around the country. Ruth’s family, farmers in Norwalk, unable to own land because they were Japanese, were forcibly sent to Santa Anita in 1942—not long after her father was taken away suddenly one day by federal agents. Ruth didn’t know where he was for the next 6 years.

The Asawas were forced to live in the stables of Santa Anita. The park was filled with Japanese Americans, forced out of their homes, to take up a residence in the stables and the newly built barracks in the parking lot. Single men were assigned spaces in the grandstand itself. The strong, permeating smell of horse and manure never left the stables for the entire five months they were there. Horsehairs floated through the air, though the horses themselves were not there.

Amidst the violence and indignity, there was—somehow—creation. The Asawas brought seeds with them, nurturing vegetables among the stables to supplement their limited meals and those of their neighbors. Things will continue to grow, with a little care. A teenage Ruth herself took painting and drawing classes from interned Disney illustrators, animators, and painters, Tom Okamoto, Ben Tanka, and Chris Ishii. A seed of a different life.

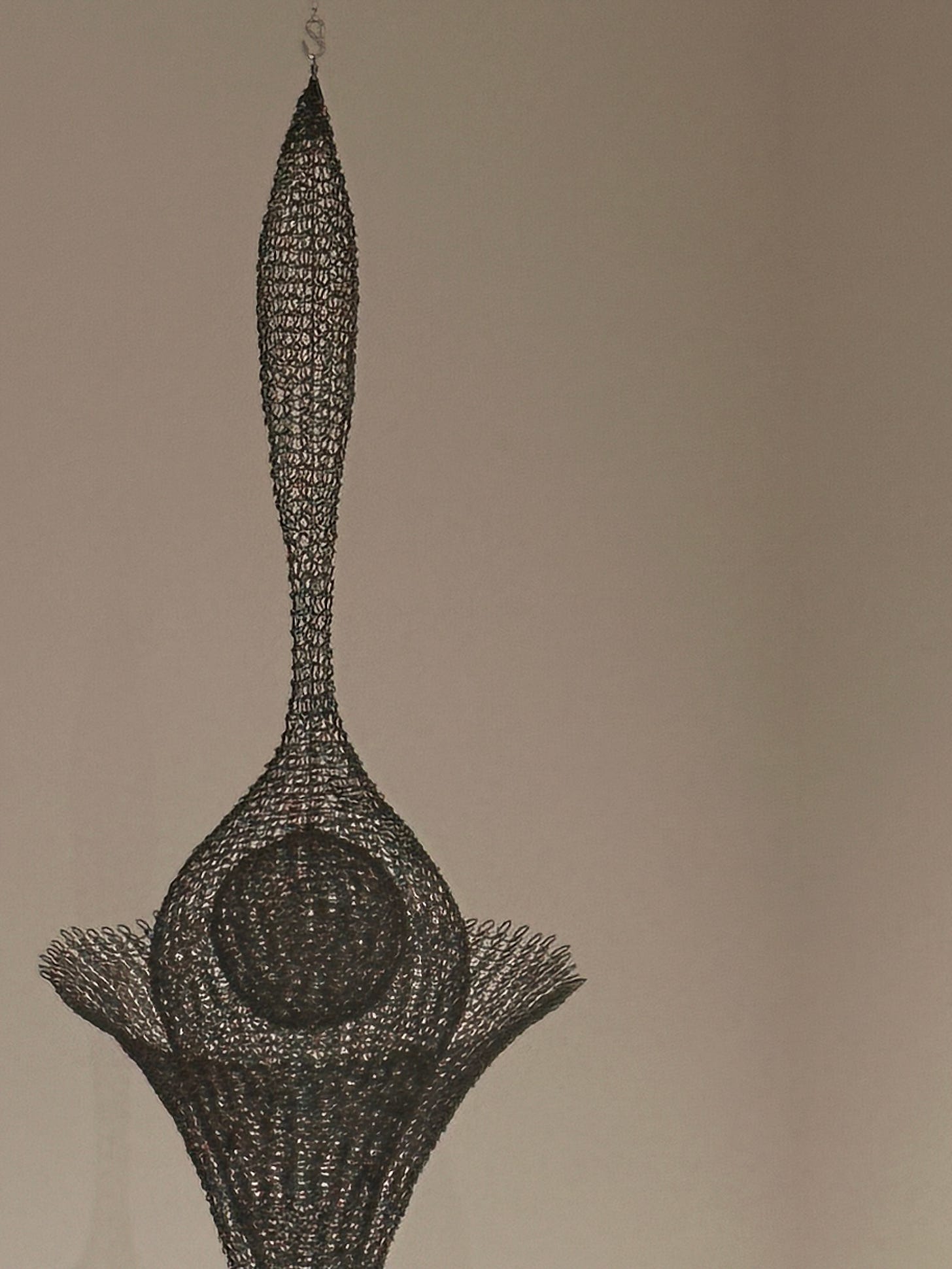

Eventually, just a year after the war ended, Ruth made it to Black Mountain College, where she would once again farm, but this time in a communal cooperative, and where she would first make her looped wire sculptures.1

Those sculptures are now on view at SFMOMA in Asawa’s first posthumous retrospective. The City is awash with the exhibition. Have you seen the Asawa show? Crowds surround those free-floating wires. Loops on loops on loops.

This week, we saw a similar story. Families separated. Forcibly removed and imprisoned for some jingoistic propaganda. We watched cops on horses trample protesters downtown.

We walk in the pattern of past footsteps. The horses run. The smell permeates, still.

Donate to The Coalition of Humane Immigrant Rights

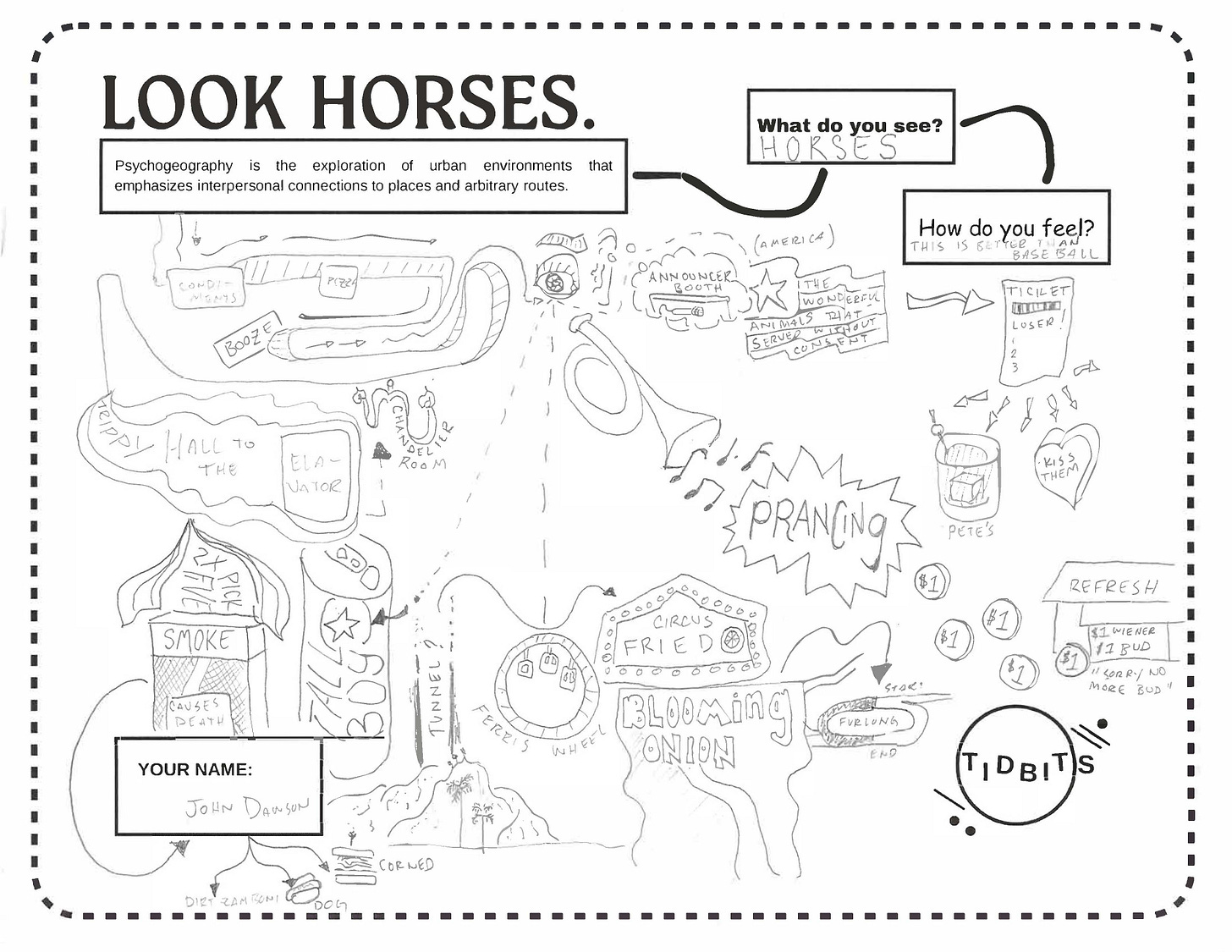

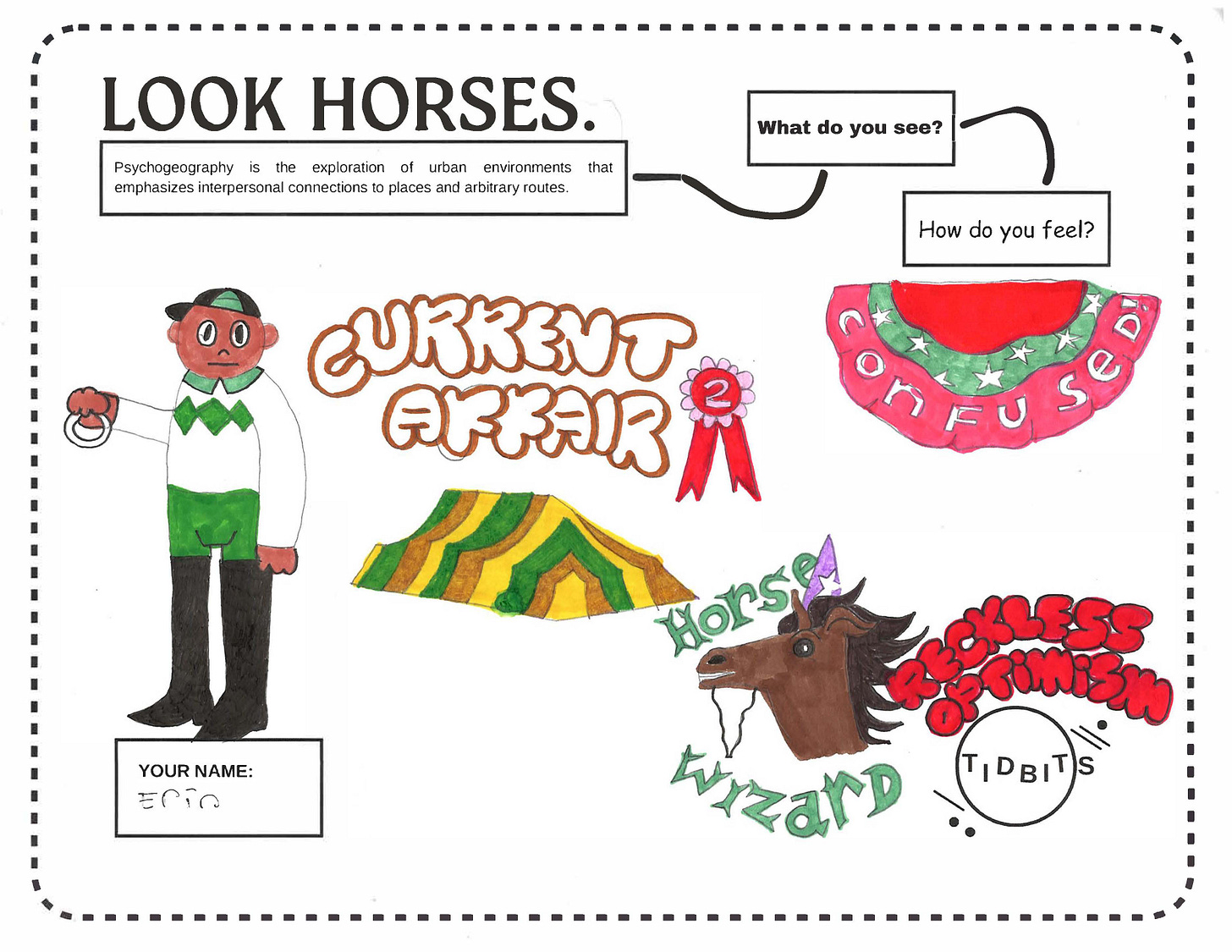

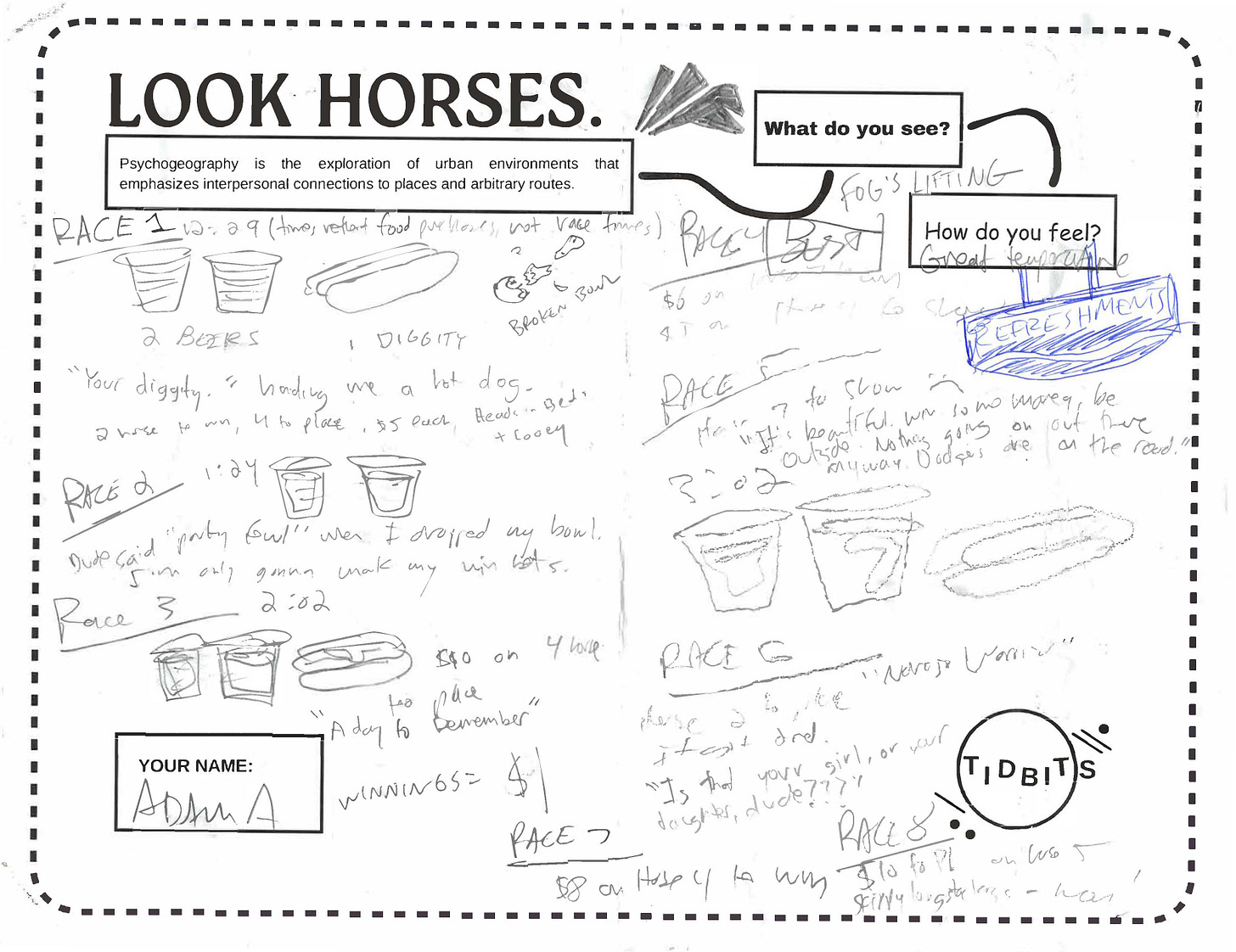

We went to Santa Anita Park on Memorial Day with a small group of friends. It was Dollar Day, with cheap beer and hot dogs. We asked them to map their experience of the park—their psychogeography of the track. You can feel them below.

References and further reading:

The Farm at Black Mountain College by David Silver. Atelier Éditions, 2024.

Santa Anita racetrack played a role in WWII internment by Alison Bell